Nassau School Public Workshop

Materials presented at the public workshop held on February 24, 2020. Read More...

Introduction to Archaeology/Historic Preservation

What is Archaeology?

Archaeology is the study of past behavior and ancient cultures. Archaeology examines all of human history, from the time of the earliest humans to the most advanced civilizations. To understand past behaviors, archaeologists study artifacts, any object modified or manufactured by humans. This assemblage often includes non-perishable or stable artifacts, such as stone tools, stone or clay vessels, glass, and metals. Archaeologists precisely record where all the clues of the past are found so they may reconstruct living surfaces, which may include house remains, fire-hearths, and refuse or garbage pits. Once the artifacts and their contexts are fully studied, researchers attempt to explain how past peoples and societies made a living and adjusted to changing social and environmental circumstances.

Why is DelDOT involved?

With the national archeology and historic preservation laws when DelDOT embarks on a project, we determine if the project has the potential to affect historic properties, which include archaeological and standing structures. If there is potential for effect, then the Department enters into consultation with the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), other preservation groups, and the public to help identify historic resources and determine if they will be affected by the project. Once it is decided that properties will be affected, then DelDOT and the consulting parties work together to limit the possible impacts to the resources. If an adverse effect on the resource will occur, DelDOT will enter into a Memorandum of Agreement with the consulting parties and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation to mitigate the resulting effects. A Memorandum of Agreement is a legally binding document that details what measures DelDOT will undertake to help offset the impacts to the historic property. This open process allows the public and DelDOT to exchange ideas, alternatives, and solutions for not only a better highway system, but for a heritage worth protecting.

Prehistory covers the time periods without a written history, which is the bulk of the human past. In Delaware, this covers the time period when native peoples inhabited the region, from about 12,000 years ago (10,000 B.C.) to about the year 1600 A.D., when Europeans first settled the area.

Archaeologists working in Delaware have created a framework for studying the prehistoric periods:

- 10,000 - 6500 B.C. Paleoindian

- 6500 - 3000 B.C. Archaic

- 3000 B.C. - 1000 A.D. Woodland I

- 1000 A.D. - 1600 A.D. Woodland II

- 1600 A.D. European Contact

Paleoindian (10,000 - 6,500B.C.)

The Paleoindian period encompasses a time when Native Americans adapted to great changes in environments, from a cold, glacial climate to a wet and dry environment, with various wooded and grassland landscapes. Archaeologists believe that the Paleoindians were highly mobile and nomadic peoples, practicing hunting of animals and gathering of plants foods. Hunted animals may have included large, now extinct mammals. The distinctive artifact of this period is the fluted point. Fluted points have been found in central Delaware. Unfortunately, many of these early archaeological artifacts are known only as surface finds; thus no intact sites, useful for reconstructing behavior and activities, are available to study.

Archaic (6,500 - 3,000 B.C.)

The Archaic period witnessed a shift from a highly mobile adaptation to one characterized by wide scale, seasonal foraging across various environmental zones. During the Archaic, habitats changed towards an oak and hemlock environment. These woods led to the increase of browsing animals such as deer, which in turn served as a hunted resource. Sea levels rose during this period as the glaciers melted, creating swampy environments. Favorable swampy environments with their animal and plant resources created more of a reliance on these foodstuffs. The number of archaeological sites of this time period increases, and new plant processing tools emerge, such as grinding stones, mortars, and pestles. While Archaic sites have been investigated in Delaware, intact ones useful for behavioral study are still rare.

Woodland I (3,000 - 1,000 A.D.)

During the Woodland I period environments changed to warm and dry, which in turn led to the increase in grassland habitats. While swamps decreased somewhat during this period, minor rises in sea level led to the formation of more brackish marshes. These environmental changes led to a more sedentary lifestyle for prehistoric groups. Areas for settlement included substantial sites on river floodplains and along swamps and marshes. The tool kits also changed, with increasing use of plant processing tools and plant harvesting tools. For the first time, stone and ceramic vessels were introduced into the tool kit, enabling more efficient cooking and storage of foods. Storage pits and hand house foundations are found more commonly from this period, indicative of a more sedentary lifestyle and possibly leading to societal ranking. Social changes are evident in increased burial ceremonialism and more elaborate and extensive trade and exchange networks of stone tools.

Woodland II (1,000 - 1,600 A.D.)

Woodland II adaptations include the more intensified use and storage of plant foods and the consumption and use of shell-fish along the Delaware shores. During the Woodland II period there appears to be an increase in population in certain areas, with more sedentism in places due to reliance on locally available plants and marine resources. Ranking of society and inter-regional interaction of social groups is noted, but these social processes do not necessarily increase in intensity compared to Woodland I practices. Changes in stone tools come are noted by the presence of triangular points in the tool kit, which are thought to be the product of the introduction of the bow and arrow. The appearance of more complex ceramic decorations and styles distinguish Woodland II groups and they may be evidence for social and cultural variability.

European Contact (1,600 A.D.)

The arrival of Europeans marks the beginning of the Contact period. It appears that Native American groups of Delaware did not participate much with Europeans or in the new colonial economies. In fact, the Contact period is marked by the virtual extinction of Native Americans through disease and violent conflicts, except for a few remnant groups which lingered throughout the historic period. Few Native American sites dating to the Contact period have been archaeologically investigated. Of those that have been treated, it appears that Native Americans incorporated and utilized some European trade goods for utilitarian purposes.

Historical archaeology covers the time period when written records are available for study. While history and archaeology both seek knowledge about the human past, history deals primarily with written accounts and archaeology mainly deals with physical remains of the past. Historical archaeologists oftentimes use written documents to help them explain past events. In Delaware, historic archaeology includes the beginning of the first permanent European settlement, from 1630 to the 1940s. The transition between prehistoric and historic times is referred to as the Contact period, when European groups first encountered Native Americans Archaeologists working in Delaware have created a framework for studying historic periods:

- 1630-1730 Exploration and Frontier Settlement

- 1730-1770 Intensified Occupation

- 1770-1830 Early Industrialization

- 1830-1880 Industrialization Early Urbanization

- 1880-1940 Urbanization Early Suburbanization

Exploration and Frontier Settlement (1630 - 1730)

In 1638, the New Sweden Company built Fort Christina, the first permanent European settlement in Delaware. In 1651, the Dutch built Fort Casimir near present day New Castle. By 1655, the Dutch were in political control of the area. By the late seventeenth century, the area had come under English control, and the population included Swedish, Finnish, Dutch and English settlers and African slaves. During this period, most people lived on farms located near waterways. These farms produced grain, primarily wheat, which was made into flour in local mills and exported. Livestock and lumber were two other major export commodities. Lewes and New Castle were the major social and commercial centers. Other scattered small settlements were made up of only a few dwellings and service oriented buildings, such as taverns and stores. These settlements were located near rivers and streams, which were the major transportation routes.

Intensified Occupation (1730 -1770)

By the middle of the eighteenth century, Delaware was rowing. There were more towns developing. Large numbers of immigrants came to the area. Industry and commerce increased. Wilmington joined New Castle and Lewes as a major settlement, and soon surpassed them, becoming Delaware's major urban center. The colony was still primarily agricultural, with flour still the major export. However people were growing more produce, such as garden vegetables. Lumbering and milling continued, and the iron industry was introduced. Waterways were still the main transportation routes, however dirt roads were being constructed for wagon travel, although road conditions were poor.

Early Industrialization (1770 -1830)

The American Revolution had a significant impact on life in Delaware during this period. British blockades limited exportation. Many military raids and skirmishes occurred disrupting the lives of Delaware inhabitants. Delaware remained primarily agricultural, however much of the land was overused by this time and was no longer fertile. Because of this, many farmers decided to go west by the end of this period. Wheat, corn and livestock continued to be grown, but farm production suffered. After the Revolution, industry and manufacturing grew. The textile industry began, snuff mills, fulling mills and grist mills were dominant. Distilleries were established to produce liquor. Home manufacture also increased during this period. As the commercial needs increased, transportation networks improved with the establishment of turnpikes and canals. Industrial growth, settlement patterns, and improvements in transportation became interdependent.

Industrialization and Early Urbanization (1830 - 1880)

Industrialization, urbanization and transportation were very important during this period. Agriculture consisted of corn farming, dairy farming, livestock production and growing of garden vegetables. The establishment of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad in 1839, along with improvements to farming techniques and machinery, helped to make Delaware one of the finest agricultural regions in the United States. The railroad allowed farm goods to get to urban markets, because they could provide quick transport. Towns grew up along the rail lines. Growth in agriculture led to the development of canneries; the needs of light in the canneries led to the development of manufactured gas, which preceded electricity, for lighting. During this period, manufacturing expanded with 380 factories in the state at the beginning of the Civil War. The Civil War had more of a social than an economic impact on the state. Some slaveholders supported Confederacy, while the manufacturers supported the Union cause. Most free African Americans in the state at the time of the War did not hold land and were tenants or day laborers. The War did little to improve the status of African Americans.

Industrialization and Early Urbanization (1880 - 1940)

During this period, the number of people employed in agriculture decreased, while the number in industry and manufacturing increased. More of the population resided in cities than in rural areas. Farmers produced more perishables, including fruits and vegetables. Poultry production and dairy farming increased during this period. Smaller farms outnumbered larger ones and much of the farming was done by tenant farmers and sharecroppers. The lumber industry and the production of charcoal was still important at the beginning of this period. Improvements in transportation occurred, including the construction of Route 113, DuPont's innovative concrete highway. By the turn of the century, there was growth in commercial agriculture, urbanism and light industry in Delaware. There was a movement toward the end of the period toward the development of suburban communities outside of urban centers.

Historic Preservation Overview

Delaware's landscape is marked by rolling hills, expansive farm fields, and miles of sandy beaches. For centuries people have lived, worked, and played on this land. The physical remnants of that activity are evident by the structures that were made, manipulated, and utilized by Delawareans. Whether these structures were houses, barns, churches, bridges, signs, hitching posts, or countless other resources, they were built as a result of roads. Increased automobile traffic over the past fifty years has necessitated repairs and the construction of new roads. These visible testaments to the past are often dangerously close to this highway work. Nevertheless, the Delaware Department of Transportation is fully committed to protecting these historic resources by consulting with the State Historic Preservation Office and preservation groups, employing a qualified cultural resource staff, and involving the public in major projects.

A mandate for historic preservation was the result of the 1966 passage of the National Historic Preservation Act by Congress. The Act created a set of laws that protects those structures, places, and objects that are historically and culturally significant to the state and nation. Historic resources are considered such when determined to be eligible for the National Register of Historic Places. The NHPA established the National Register as a list of the significant historic properties in the United States. Section 106 of that act ensures that federal agencies follow certain steps in order to limit the impacts to these eligible properties. Therefore, the Delaware Department of Transportation has developed policies to not only to follow Section 106, but also to become a partner in preserving Delaware's heritage.

Pursuant to Section 106, when DelDOT embarks on a project, we determine if the project has the potential to affect historic properties, which include archaeological and standing structures. If there is potential for effect, then the Department enters into consultation with the State Historic Preservation Office (SHPO), other preservation groups, and the public to help identify historic resources and determine if they will be affected by the project. Once it is decided that properties will be affected, then DelDOT and the consulting parties work together to limit the possible impacts to the resources. If an adverse effect on the resource will occur, DelDOT will enter into a Memorandum of Agreement with the consulting parties and the Advisory Council on Historic Preservation to mitigate the resulting effects. A Memorandum of Agreement is a legally binding document that details what measures DelDOT will undertake to help offset the impacts to the historic property. This open process allows the public and DelDOT to exchange ideas, alternatives, and solutions for not only a better highway system, but for a heritage worth protecting.

A circa 1815 granite milestone on Concord Pike: (Route 202) informing travelers on the Wilmington

and Great Valley Turnpike that Wilmington was only two miles away.

Van Buren Street Bridge: Brandywine Park in Wilmington

Downtown Delaware City: The adaptive reuse of historic buildings to serve modern commerce.

Port Penn Post Office

Victorian Dover: A row of Victorian gothic homes in Dover. Victorian architecture was a popular style in the late nineteenth century, and is found throughout Delaware.

Hitching Post: One of the many surviving hitching posts in Victorian Dover.

Wyoming Train Station: The train depot in foreground and houses across the track testify to the immense influence of the railroad in the development of towns like Wyoming in the state.

The Three B's Store: A typical small family business located in downtown Wyoming.

The Scientific Process of Archaeology

Mention "archaeologist," and the image of pit-helmeted workers in exotic locales comes readily to mind. Egypt, Mesopotamia, Mexico, and the American Southwest are all places where it is easy to imagine archaeologists at work. But archaeologists digging in Delaware? What would archaeologists seek here? Why would they be interested? The story of the Thomas Dawson Site gives some answers to such questions.

Teaching the process of scientific archaeology to school children.

Archaeologists study the material culture of past societies. Material culture is the portion of the physical world that has been shaped by people through intentional action in the context of society. Examples of material culture include:

- Tools

- Playthings

- Containers

- Buildings

- Yards and Gardens

- Vehicles

- Roads and Bridges

- Foods and Medicines

- Religious Objects

- Sculptures and Paintings

- Musical Instruments

The objects people make and use, and the ways they arrange these objects in space reflects the world in which they live and the ways in which they think about this world. Archaeologists study material culture and the spatial relationships among the objects they find to gain knowledge about the past.

Historical archaeology employs written records in combination with the study of material culture to learn about American history.

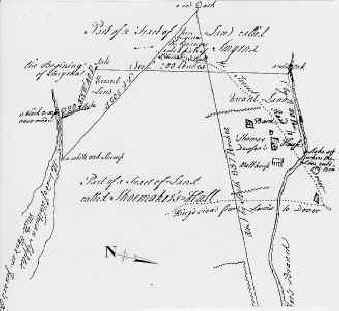

1745 Surveyors Plat

Although the United States has a vast storehouse of documentary information concerning its history over the past several centuries, written records do not reveal all aspects of the past with equal clarity. Such records tend to be richest in reference to great events, the public lives of leading citizens, and the activities of political and governmental institutions. The everyday lives of everyday people tend to be less thoroughly reflected in historical records. By studying the remains of past material culture that people lost, discarded, or abandoned in their day- to-day lives, new insights can emerge concerning the details of the American past. These details constitute the fabric within which and through which the broad patterns of American history developed.

The Evidence of Archaeology

Pottery Shards

Artifacts

Individual objects that people have made or modified. Pottery sherds, bottles, individual bricks, and meat bones are all examples of artifacts.

Archaeologists excavating features.

Features

Discrete arrangements of objects that are the product of some specific human activity. Unlike artifacts, features generally cannot be moved from the spots where they are found without being seriously damaged. Examples of features include building foundations, walls, pits, and trenches.

Deposits

Soil and other materials laid down by humans or by natural agencies such as flowing water. Archaeologists analyze the nature and contents of deposits to reconstruct a history of a site.